In 1932 picketing farmers shut down Council Bluffs highways in a tense stand-off with law enforcement. This is the story of how years of depressed prices and government inaction led farmers in western Iowa to mount a populist revolt.

During the First World War, Herbert Hoover served as America’s “food czar” in charge of securing the nation’s food supply. As agricultural production in allied countries plummeted, Hoover implored American farmers to increase yields. With demand and prices high, farmers did just that, often borrowing money to buy more land and new equipment. But when the war ended, as Europe and Russia recovered and began to feed themselves again, demand dropped off and food prices plummeted, forcing indebted farmers in the United States to grow more and earn less. While many in the United States enjoyed the excesses brought about by the economic prosperity of the Roaring Twenties, desperate farmers, unable to afford coal, burned nearly-worthless corn in their stoves, causing the countryside to smell of popcorn.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Hoover (now President) called it a “depression.” And with the coming of the Great Depression, came calls from desperate bankers seeking to collect on those war-era farm loans. The local newspaper was filled with bankruptcy notices and advertisements for farm foreclosure sales, as banks seized property and equipment. Many Iowa farmers, however, were not willing to hand their inheritance over to bankers; farmers in Logan, Storm Lake and elsewhere organized mobs to chase off bankers and lawyers. In Le Mars, five hundred farmers stormed the county courthouse and threatened to hang a judge for approving farm foreclosures.

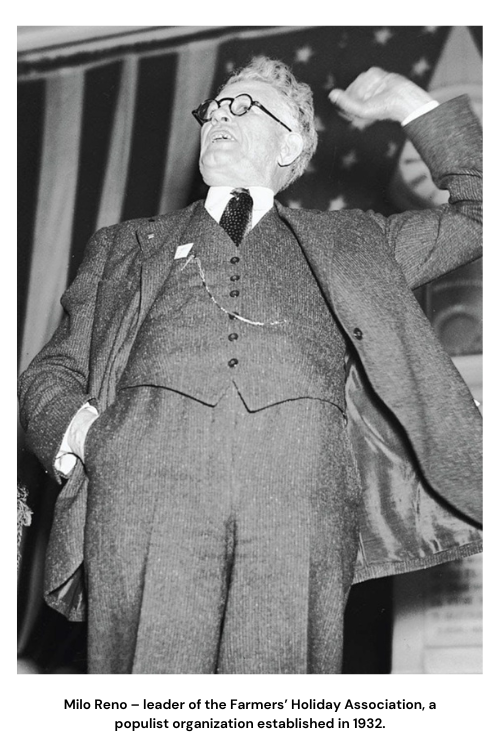

The National Farmers Union’s lobbied for aid and tariff reform in 1932, but no legislation was passed. Frustrated with the lack of results, Milo Reno, the former president of the Iowa Farmer’s Union, decided to take direct, radical action. Forming a protest movement known as the Farmers’ Holiday Association, Reno encouraged farmers to stop selling and buying - to withhold crops from the market in order to draw attention to the plight of farmers. “We’ll eat our wheat and ham and eggs,” Reno said, “and let them eat their gold.”

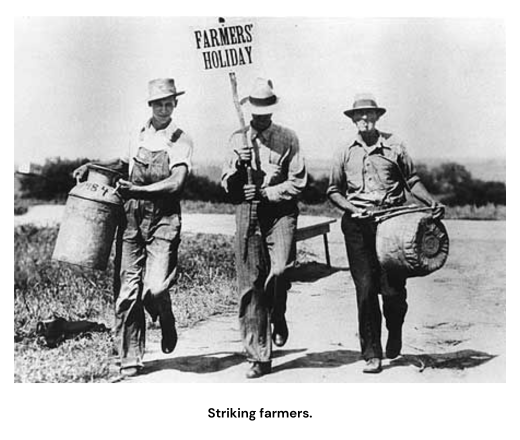

Crop prices in 1932 were less than a third of what they had been in 1920 - so low that farmers were paying more to produce their corps than they earned from selling them. In May of 1932, hundreds of angry farmers met in Des Moines to discuss solutions to what they called “economic slavery.” The group dismissed Hoover’s campaign pledges as “lollipops and pacifiers to keep you quiet.” Tired of appealing to state officers (whom one speaker dismissed as “politicians who don’t give a cuss about [farmers]”) the group unanimously endorsed a resolution to refuse to buy or sell anything until the prices of their crops rose above the cost of production.

As the Farmers’ Holiday movement spread from town to town, Henry Wallace and other prominent Iowa landowners became uncomfortable with the growing populist insurrection, though they understood the anger behind it and supported many of the movement’s objectives. Locally, mass Holiday meetings were held in Council Bluffs, Logan, Clarinda, Modale, Red Oak, and elsewhere. Farmers organized, urging everyone in attendance to withhold products to relieve the surplus that was being poured into the markets by desperate farmers. Overflow audiences came to hear about the idea, but leadership from the State Grange discouraged members from attending, stating, “Getting higher farm prices through a farmers’ strike is impossible.” The Iowa Farm Bureau did not issue a statement, though it was generally known that the organization was also critical of the idea.

Far from being discouraged, Milo Reno, the head of the Holiday movement, attacked members of the Farm Bureau in mass meetings. To angry crowds, Reno argued, “If farm organizations cannot, at this time, fearlessly take the steps necessary to save agriculture there remains no reason for their continued existence.” In Des Moines, at a meeting of two thousand farmers, leaders of the movement announced the “Holiday” would begin in the summer of 1932. Farmers, labor leaders, agricultural organizations, and bankers discussed the issue at length. In the end, the group resolved, “If we cannot obtain justice by legislation … no other course remains than organized refusal to deliver the products of the farm at less than production costs.” Farmers in attendance pledged to “stay at home – don’t sell.” And as they would not be selling, the Farmers’ Holiday organization, in a show of solidarity, offered to ship train cars of food to Washington D.C. to feed the “Bonus Army” marchers – a massive gathering of war veterans who had camped in the nation’s capital to pressure Congress into awarding a promised bonus for their wartime service.

In Iowa, the Farmers’ Holiday spread to thirty-four local groups representing eighty-eight counties. Reno and other members of the movement wrote to Iowa papers to explain their intentions, declaring that there was “nothing revolutionary or un-American in the move,” and that they hoped only to “bring consumers to a realization of the importance of the farmer in the economic system.” It was estimated that half a million Midwest farmers had signed the Farmers’ Holiday pledge.

Logan was among the first communities in western Iowa to strike. Picketers lined roads, encouraging motorists to stay home. The newspaper reported that if the strike had any effect it was not discernible as merchants kept shelves stocked and prices level. But the following week the Department of Agriculture released figures on hog market receipts that showed a 10 percent decrease in supply and a corresponding 10 cent price advance. Similar reports came in from grain elevator companies who were unable to keep their houses full of oats. Looking to these as leading indicators, the protesters were convinced the effects of the Holiday were beginning to be felt.

The newspapers reported “relative calm” with the strike underway in farming communities across the state, and produce dealers in Council Bluffs reported seeing little evidence the strike would affect business. “Most of the farmers around here seem to be opposed to the strike,” one produce-seller said. “They say they can’t afford to throw away any of their stuff as they need what few dollars they can get to buy other supplies.” Striking farmers found, though many had pledged to stop selling, relatively few followed through. In an effort to stop others from selling, twenty farmers in Waterloo Iowa attempted to forcibly shut down a creamery, threatening to dump its cream, and warning the manager to “stop deliveries or something would happen.” The gathering of angry farmers was dispersed by the Sheriff, but returned the following night to make good on their threats.

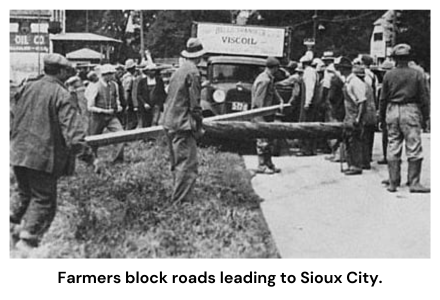

In Sioux City and Boone, farmers blockaded all highways leading into town, successfully preventing farm produce and livestock from reaching the city by truck. Authorities escorted trucks through the picket lines until it became apparent that their efforts to break the picket lines were going to result in bloodshed, and the sheriff began advising truckers to return home.

An automobile driver in Sioux City, angered by the delay, fired a revolver into the crowd of farmers. The newspaper reported that the “effects of the blockade were strikingly apparent at the stockyards.” The only livestock on the market had arrived by rail, and the stockyards were nowhere near capacity. With blockades at every entry to Sioux City, stockyard and produce markets receipts plummeted. The picketers, however, were sympathetic to the plight of their fellow farmers, and allowed few of the more desperate sellers through the blockade.

Emboldened by their success in Sioux City, farmers expanded their picket blockades to include railroad stations. The Holiday association issued notices to dozens of creamers, packers and law enforcement agencies. When the Sheriff in Waterloo advised truck operators to arm themselves, strikers armed themselves with spiked planks and threshing machine belts for stopping trucks that tried to run the blockade.

On August 20th, the Sioux City Milk Producer’s association met with striking farmers and negotiated an 80% price increase, and the farmers began allowing dairy trucks though the blockade, but still turned away produce and livestock shipments. The Sheriffs of Woodbury and Plymouth counties maintained a force of several hundred deputies to escort trucks though the lines, but no truckers asked for assistance as farmers who were not a part of the movement were reluctant to risk personal injury or loss of product.

Members of the Farmers’ Holiday movement considered the milk price increase proof that their efforts were working. Hundreds of Farmers from five Iowa counties met in Dunlap, Iowa on August 22nd to discuss plans to picket roads leading to Omaha. Milo Reno, the movement’s founder, declared the growing movement a success, but noted that, the real progress was not measured in the percentage of products held from markets. “The real progress is that not only farmers but all groups everywhere are beginning to realize the absolute justice and the absolute necessity of our aims,” Reno said. The strike was intended to establish in the minds of the public the idea that “the farmer, as the producer of the one absolute necessity to continued existence of mankind, is placed in a position of responsibility to mankind shared by no other producer.” Reno even had some limited success in getting local government on board, including the governor of Minnesota, who announced he was prepared to take action to restore farm prices, even to the extent of declaring martial law. But officials in Council Bluffs were not as tolerant of the picketers.

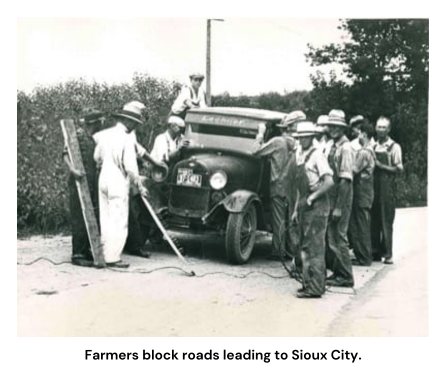

When four hundred farmers met at the fairgrounds in Missouri Valley, a ninety percent majority voted to picket highways leading into Council Bluffs. Farmer Jim Hawn of Woodbine said, “I’m over 60 years of age, and I’ve lost everything but my tongue, but I’m sure going out and use it.” The farmers met with local law enforcement to announce their intentions, and promised that their protest would be orderly and peaceful.

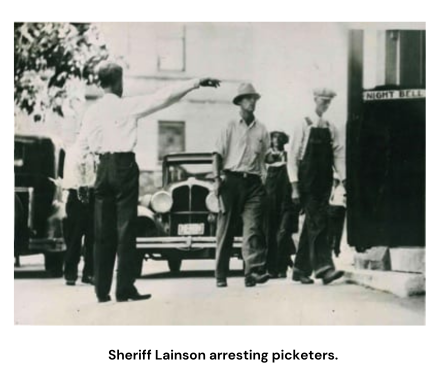

In late August, a group of farmers began picketed on Highways leading into Council Bluffs. Sheriff P.A. Lainson warned the group that they would not be allowed to block traffic, as was done in Sioux City. Carrying signs and shouting slogans, the group hoped to persuade farmers to turn around. Some motorists who stopped to listen to the picketers were persuaded to turn around. However, some motorists were not persuaded, or simply drove through the picket line. In defiance of the Sheriff’s orders, the picketers began placing timbers on the highway to block trucks from delivering to markets in Council Bluffs. When a group of over one hundred farmers shut down Highway 34 near Iowa School for the Deaf, Sheriff Lainson considered it an illegal act of violence and a promise broken. Calling the farmers “hoodlums,” Sheriff Lainson said, “They have thrown down the gauntlet … and I’m going to fight it out if it takes 5,000 deputies. If the Pottawattamie county jail bulges with pickets it will have to bulge.”

The group was not deterred by this tough rhetoric, and began knocking down telephone poles to block produce trucks. The sheriff moved quickly to swear in ninety-eight special deputies, arming each with a club. Orders were issued for pickets to move from the highway, and the deputies were instructed to arrest anyone who did not comply. The hiring of the special deputies was authorized at an emergency meeting of the Pottawattamie County Board of Supervisors. The salary was $3.50 per day, and no limit was set by the board on the number to be employed by the Sheriff. When the Sheriff threatened to file conspiracy charges, some local organizers of the Farmers' Holiday movement dissociated themselves from the Council Bluffs picketers, stating that the group had gotten out of control and was acting against the spirit of the movement.

Vehicles carrying farm products to Council Bluffs were forced to either unload their produce or turn back. A representative of the Nebraska-Iowa Co-operative milk associated showed up to plead with the picketers, but the farmers insisted they would hold until a deal was worked out with the Holiday leaders in Des Moines. “We are in sympathy with farmers seeking higher prices,” the dairy representative said, “but you must organize and peacefully work to the end you desire.”

The State Sheriff in Nebraska, announcing he would not allow interference with inter-state shipments, mobilized officers across the state and advised county offices to notify federal authorities and swear in extra deputies as necessary. Reports were coming in of pickets in Danbury, Rockford, Mapleton, Waterloo, Fort Dodge, Des Moines, Onawa, Spencer and elsewhere. Some protests were orderly and peaceful, while others ended in violence.

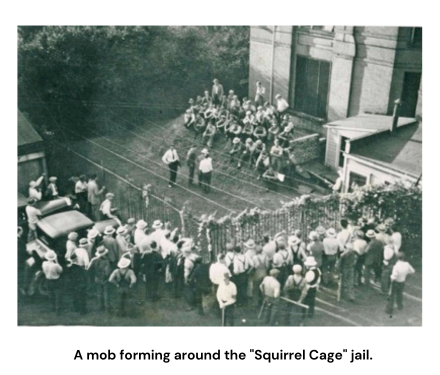

In Council Bluffs, forty-nine picketers were arrested and jailed. The mood was tense as two hundred resumed picketing on August 25th. The Sheriff upgraded the arsenal of the special deputies, trading their clubs for riot guns and sub-machine guns. It was reported that a group of 1,000 farmers was traveling south to Council Bluffs to aid the picketers and to break arrested farmers out of the “Squirrel Cage” jail. While training with their new riot guns, two special deputies where shot - one later died from the wound. Sheriff Lainson repeated his promise to “arrest every man found picketing and bring him in for unlawful assembly.”

Fearing that the farmers would storm the jail, Deputies were authorized to shoot-to-kill. The Daily Nonpareil published a warning to its readers advising them to stay away from the jail for their own safety.

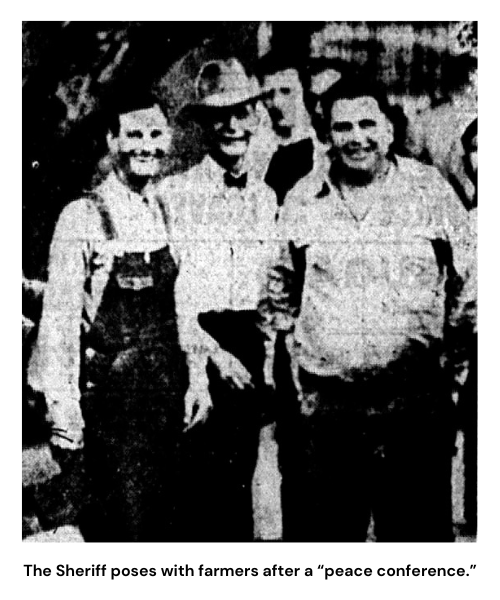

The number of protesting farmers swelled to 1,500 at Highway 34 alone. As the caravan of an estimated 1,000 farmers approached Council Bluffs to storm the jail, the Chamber of Commerce called for an emergency “peace conference.” This conference, held at the Hotel Chieftan, was attended by the Chamber President, the Mayor, the Police Chief, the Sheriff, and a delegation of nine striking farmers. The meeting was a success by all accounts. After three and half hours of negotiation, the farmers offered to withdraw ninety percent of the group if the Sheriff would aid and support a small group of peaceful protesters.

After days of increasingly intense stand-offs, tensions seemed to ease, as the Sheriff was photographed standing side-by-side with the smiling farmers. The National Chairman of the Farm-labor party and an attorney for the Iowa Holiday movement were allowed to visit the Squirrel Cage jail, where they informed the imprisoned farmers that they were negotiating for their release. The following day, a group of wealthy farmers raised $5,000 to bail the farmers from jail.

With the farmers free, the Mayor met with the south-bound caravan of farmers as it entered town and convinced the group to disperse. The tension had eased, but the strikes continued and Sheriff Lainson added fifty more deputies. As part of the agreement reached at the peace conference, the Sheriff agreed to furnish deputies to assist the farmers in peaceful protest while he waited for the Attorney General’s Office to rule on the legality of the protest. When a major labor union passed a resolution in support of the strike movement, several union men employed by Sheriff Lainson as special deputies resigned, turning in their badges at the courthouse. The number of deputies and pickets gradually diminished.

One by one, towns in Western Iowa began arranging meetings between business leaders and striking farmers. In Council Bluffs, organizers came to agreements with truckers associations and Robert’s Dairy. In Clinton, picketers negotiated a series of price increases for milk. In Shenandoah, strikers agreed to withdraw in exchange for daily radio time to air a “persuasion campaign” for the movement. And strikers in Pottawattamie County reached a deal with Harrison County stockyards that would allow cattle in under certain conditions, one of them being that all shipments needed to be approved by the Holiday association.

The Farmer’s Holiday failed to materialize as a national force, and failed to achieve many of its stated goals, but it did succeed in pressuring authorities to take action. In the end, the Farmer’s Holiday was least successful in its goal to raise prices, and most successful in its goal to raise awareness of the plight and value of the American farmer.

Nine months after the protests in Council Bluffs, Congress passed the first farm bill as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Just as the Holiday movement sought to raise prices by limiting supply, the Agricultural Adjustment Act launched a program to raise agricultural prices by paying farmers to limit production. The Holiday movement quietly fell apart as farmers were mollified by checks from the Department of Agriculture.

Popular support for Milo Reno, founder of the Farmers’ Holiday Movement, waned following a violent incident in Le Mars that made the front page of the New York Times. Henry Wallace, Roosevelt’s Secretary of Agriculture, presented a plan that was seen as moderate when compared to the radical restructuring proposed by Milo Reno.

Stripped of influence and followers, Milo Reno railed against Roosevelt’s farm bill. Ironically, the bill may not have materialized without the influence of his Farmers’ Holiday protests which drew national attention to the desperate plight of America’s farmers during the Great Depression.

Click HERE for more information on Council Bluffs History.